The Fair Sentencing Act of 2010

S. 1789, known as the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, passed in Congress on July 28, 2010, and President Obama signed the bill into law on August 3, 2010.

In summary, this new law did four main things:

(1) it changed the statutory 100:1 ratio in crack/powder cocaine quantities that trigger the mandatory minimum penalties under 21 U.S.C. § 841(b)(1);

(2) it reduced the statutory 100:1 ratio to 18:1 by increasing the threshold amount of crack cocaine to 28 grams (for the 5-year mandatory minimum) and 280 grams (for the 10-year mandatory minimum);

(3) it did away entirely with the 5-year mandatory minimum for simple possession of crack; and

(4) it directed the U.S. Sentencing Commission to amend the Sentencing Guidelines to reflect the statutory changes made by the new law.

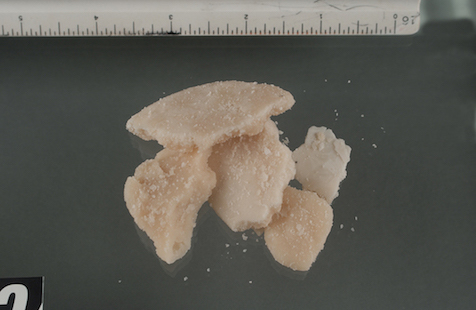

Before the Fair Sentencing Act passed, the smallest chip shown here would get you 5 years minimum. After the Act passed, it would take about as much as this whole crack cookie to get you 5 years.

In July, 2011, the United States Sentencing Commission voted to make the new Guidelines mandated by the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 retroactive. The Commission set a retroactive effective date of November 1, 2011, which means that starting on that date, but not before, federal Judges had jurisdiction to begin granting motions for retroactive application of the Guidelines.

However, it is important to note that Congress failed to make the mandatory minimum provisions of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 retroactive at that time. This is confusing to many, and understandably so. The best explanation I can give is this: While Congress authorized the Sentencing Commission to reduce the crack guidelines and to make those guidelines retroactive, Congress did not make its new mandatory minimum provisions retroactive. Consequently, those who received a mandatory minimum are not eligible at this time, unless they received a sentence reduction under 18 U.S.C. 3553(e) for cooperation, either under 5K1.1 of the Sentencing Guidelines or under Rule 35 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure (or unless they can still earn one). That is the only way to “bust the mandatory minimum” after sentencing. (In February 2015 the Smarter Sentencing Act of 2015, which would expand who can apply for a sentence reduction, was introduced in Congress, but it has yet to become law.)

Still, the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 and the related Sentencing Guideline changes made thousands of inmates eligible for a sentence reduction. Many inmates that are eligible have yet to take advantage of this! Your loved one may be one of them.

If you know someone serving a sentence in federal prison for crack cocaine, then you will want to read this. The information you gain on this one page could set a friend or family member on the path to being released from prison YEARS sooner than expected!

In addition to some history on the federal crack laws (below), I will also be posting additional information, including some answers to frequently asked questions and more changes in drug and sentencing laws, on our law blog. You can also follow me on Facebook or Google+ or subscribe to our blog feed.

Background

In 2007, the United States Sentencing Commission began debating and taking public comment on proposed amendments to the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines. Among the amendments being considered was one to effectively reduce the length of sentences given to crack or cocaine base offenders. The proposed amendment essentially provided that any particular quantity of “relevant conduct” quantity of crack would fall two levels lower on the Sentencing Guideline Table than it did previously.

The amendment has some historical background. Back when the law was passed that established how long sentences were to be for various amounts of various substances, it was determined that “crack” cocaine or “cocaine base” was so much more insidious than regular “powder cocaine” that sentences in crack cases ought to be much higher than sentences in powder cocaine cases. As a result, the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines were established setting up a 1 to 100 ratio between crack and powder cocaine. What this meant was that someone responsible for 10 grams of crack would receive the same sentence as someone responsible for 1000 grams (1 kilogram) of powder cocaine.

It quickly became obvious to everyone involved that there was a serious problem with this disparity in the treatment of crack and powder cocaine offenders, namely that crack cases primarily involve black or African-American individuals, whereas powder cocaine cases primarily involve white individuals. From the very beginning, a clamor arose from various corners of society regarding the injustice of this disparity. Civil rights groups, sentencing advocacy groups, minority advocacy groups, and criminal defense attorney groups began to see that, across the board, black defendants with a particular quantity of crack were receiving much harsher sentences than their white counterparts sentenced for the same quantity of powder cocaine.

The result of years of such clamoring was the proposed amendment to the crack provisions of the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines.

The “Crack” Amendment and Retroactivity

On November 1, 2007, the amendments to the guidelines were passed, with the Sentencing Commission stating that this was a first step toward eliminating the racial disparity set up by the Sentencing Guidelines. As of November 1, 2007, defendants sentenced in crack cases began receiving the benefit of the new Sentencing Guideline provisions. Defendants previously sentenced, however, did not.

What followed was an additional period for comment and debate concerning whether to specifically make the “crack” amendment retroactive. Specifically, the question for the U.S. Sentencing Commission was, “Do we allow those previously sentenced under this unjust and inequitable guideline suffer the injustice, or do we allow this amendment to be applied retroactively so that defendants previously sentenced in federal crack cases can ask the sentencing Judge to reduce the previously-imposed sentence to bring it in line with the amendment?”

After debate, public comment, and a public hearing in Washington, D.C., on December 11, 2007, the U.S. Sentencing Commission did vote in favor of making the amendment retroactively applicable, but they made a statement that the amendment did not become retroactive until March 3, 2008.

Practical Implications

All of this has several implications for those who were sentenced in federal crack cases before November 1, 2007.

First, the inmate may be eligible (even now, five years after it went into effect) to request that his sentence be reduced. As of October, 2013, inmates who have gotten sentence reductions have had them shortened by an average of 29 months. Statistics and estimates vary concerning the number of eligible inmates; in 2007, the U.S. Sentencing Commission estimated that 19,500 inmates then incarcerated in federal prison were eligible for a reduction in their sentence. By the end of 2011, it was estimated that around 12,000 inmates were still eligible for a sentence reduction.

Second, inmates who were sentenced before the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in U.S. vs. Booker on January 12, 2005, may request a further reduction in their sentence based on factors that sentencing Judges were unable to consider before Booker.

There are some individuals who were technically ineligible for relief under this amendment: 1) those sentenced to a statutory mandatory minimum sentence; 2) those whose sentence was imposed pursuant to the Career Offender enhancement where the Career Offender or Armed Career Criminal enhancement increased the total offense level; and 3) those whose total offense level was less than 12 or more than 43. There is some authority that suggests that there may be exceptions to the above — limitations that must be handled on a case-by-case basis. See the “Note on Eligibility” at the bottom of this page.

It should be noted that, although someone may be technically eligible to request a reduction in his or her sentence, it is ultimately within the sole discretion of the Judge whether to grant the request or not. (Consequently, do not trust anyone who claims they can guarantee you a favorable result.)

However, it appears that a very large number, and perhaps a majority, of those who were sentenced in crack cases are eligible. In short, for those to whom this amendment applies, this is an opportunity for meaningful relief.

How it Works

Here is how it is likely to work out, using a hypothetical example. Let’s say that an individual convicted in a crack possession or conspiracy case is sentenced based on “relevant conduct” quantity of 500 grams of crack, and he or she has 4 criminal history points. The sentence range corresponds to Offense Level 36 and Criminal History Category of III. And based on this, the individual, then, before November 1, 2007, receives a sentence of 240 months (20 years).

Under the “crack” amendment, the individual would then be eligible to ask the sentencing Judge to give him a new sentence based on the amendment, and the appropriate sentencing range would now be 188 – 235 months. This means that, should the Judge, in his discretion, grant the motion, the 240 month sentence could be reduced to 188 months, for a reduction of 52 months (over 4 years). This is a significant reduction.

Further, if this individual was sentenced before January 12, 2005, the sentence may even be reduced further based on new factors that the Judge would be allowed to consider under Booker.

What to Do Now?

Have the inmate’s Presentence Investigation Report (PSI or PSR) reviewed by an attorney who is very familiar with this sentencing guideline amendment to see if he or she is eligible to request a sentence reduction. I can provide this review for eligibility for a fee of $500.00.

An inmate who believes he may be eligible for a reduction in his or her sentence based on the “crack” amendment should find out for sure if the amendment is applicable to him or her. An attorney is the only one who can determine whether someone is technically eligible. The inmate should contact an attorney who is very familiar with the “crack” amendment and who is familiar with procedures related to seeking this particular specialized kind of post-conviction relief. The attorney will need to review the inmate’s Presentence Investigation Report (sometimes referred to as the “PSI” or the “PSR”) to determine eligibility.

If a trusted friend or family member does not have a copy to forward to the reviewing attorney, then a letter should be sent to the attorney who handled the case before the U.S. District Court requesting that the PSI be forwarded to the attorney reviewing the case for applicability of the “crack” amendment.

If the inmate is eligible, an attorney can file a motion under 18 U.S.C. Section 3582, in which the attorney will set forth factual and legal arguments for granting a reduction in the inmate’s sentence. Although the inmate may file such motions on his or her own behalf, I advise all inmates to hire competent legal counsel. A competent attorney will be aware of what the Judge is likely to consider most relevant in making his decision, and he or she will be aware of what pitfalls to avoid. Additionally, matters handled by attorneys are much more likely to be successful than matters handled pro se (meaning the inmate files the motion on his own behalf).

If you know someone who would like me to review their case to see whether any relief is available to him or her, have the individual’s Presentence Investigation Report sent to me. Alternatively, forward my information on to this person, contact me directly, or provide me with the individual’s name, registration number, and address, and I will give more information that will help expedite the process of determining eligibility and preparing to file the motion. While I am reviewing the PSI, I can review for other issues which could mean additional years off the sentence.

Note on Eligibility

The U.S. Sentencing Commission’s original estimate (in 2007) was that 19,500 individuals were eligible to seek relief under the retroactive “crack” amendment. Since then, the Commission has indicated that this number is both over-inclusive and under-inclusive. What this means is that some of the people on the “list” are actually not eligible, and others who are eligible are not on the “list”. (By the way, we are now told that there are a number of unofficial lists generated by different offices, all of which are admittedly both over-inclusive and under-inclusive. Estimates in November, 2011, when the guidelines became retroactive, were that 12,000 people might still be eligible.) Practically, it means that there are likely a large number of people who may actually be legally eligible for relief who may be technically ineligible under the language of the Amendment.

Finally, and perhaps most encouraging, is the fact that without exception, defense attorneys are being exhorted to file Section 3582 motions on behalf of their clients who were designated as Career Offenders regardless of whether the enhancement affected their base offense levels, and in spite of the language of the Amendment to the contrary. The arguments in favor of this are a bit complex, but suffice it to say that I will no longer be recommending to potential clients that they shelve their hopes of seeking relief under the “crack” amendment just because they received a Career Offender enhancement. The individual should know that motions in such cases will be vigorously opposed by both the U.S. Attorney’s office and the U.S. Probation office, but a good attorney will be able to help the Judge understand that he has the discretion to grant relief in such cases, and will make every effort to give the Judge the information he needs about his client to make the Judge want to exercise such discretion.

I can handle these cases in any Federal Court in the United States.

Feel free to contact me with any questions you may have. Please call me at (512) 693-9LAW, or, to email me, you may click on the “Contact Us” link here or at the top of the page and send me an email directly from this website.

by Chad Van Cleave